Coping with religious plurality in the early modern age: This could be the title of the interview that Louise Zbiranski, the outreach officer of the research group “Dynamics of Religion”, has conducted with Dr Andreea Badea and Prof Dr Alexandra Walsham. Andreea Badea is a post-doctoral researcher at Goethe University and member of the POLY Research Group; Alexandra Walsham is Professor of Modern History at the University of Cambridge. She was a POLY Research Fellow from May to July 2023. You can find a German version of the interview here.

LOUISE ZBIRANSKI When we talk about religious diversity, the first thing that usually comes to mind is the coexistence of members of different religions. This is why Andalusia, where Muslims, Jews, and Christians lived together for generations, stands as the classic example for religious plurality in the pre-modern era. However, the question of how religious plurality was negotiated also arises for regions that at first glance seem dominated by one of the major religions. After all, these religions were and are diverse in themselves and characterised by different currents and interests, a situation which posed and still pose challenges for their own religious institutions and authorities. Your research centres on this inner plurality in early modern Christianity. Perhaps you could briefly outline the aspects of religious diversity that you are studying?

ALEXANDRA WALSHAM My work focuses on the British Isles primarily, but sets developments in the context of the larger European framework. With regard to the British Isles, the first thing to say is that it is a fallacy to think of the late Middle Ages, i.e., roughly the time between the thirteenth and the fifteenth centuries, as a monolithic unified religious culture. But certainly, in Britain as elsewhere, it is the subsequent Reformation, that unleashes the spectre of unwanted plurality, and it is that period that my research centres on. I am particularly interested in how people lived with this plurality. But before I go into more detail, it seems helpful to recall some of the historical context of this diversity in the British Isles.

We need to remember, first, that this plurality is the consequence of the state dictating a major change in religion and that many individuals had to navigate a series of changes in the mid-sixteenth century as a result of the deaths of monarchs. In particular the short-lived reigns of Edward VI (King of England and Ireland from 1547 to 1553) and of Mary I (Queen of England and Ireland from 1553 to 1558) induce a series of reversals of the official policy on religion that in themselves create the ingredients for plurality.

Then there are other aspects of the Reformation in Britain, particularly in England, which produce a special situation. With the Church of England, a broad-based institution was formed within which the priority was to enforce outward conformity, outward observance rather than seek to coerce inner belief—that is at least the claim of that regime. And to an extent it is true: Catholics were able to continue to practise Catholicism at home, albeit surrounded by challenging circumstances. But provided they attended church, even irregularly, they could navigate their way around the law.

The repercussions of this rather imperfect reformation in England create circumstances in which other groups within the Protestant establishment are discontented with the type of religious settlement that has been established. That means that within the institution, there is dissent, there is intra-Protestant dissent, and that itself is one of the major factors in bringing about the Civil War, which breaks out around 100 years after the Reformation in 1642. It had the effect of increasing the breakdown of control so that inter-Protestant dissent was entrenched further. Dissent, that is to say Protestant-sectarian dissent, becomes an ineradicable feature of English and British society. The repercussions of that lead ultimately to the attempt to find a way of accommodating some forms of plurality in the so-called Act of Toleration of 1689.

After 1642, inter-Protestant dissent was entrenched further. Dissent, that is to say Protestant-sectarian dissent, becomes an ineradicable feature of English and British society.

– Alexandra Walsham

LOUISE ZBIRANSKI Andreea, you are working on what appears to be the monolithic religion par excellence—the Catholic Church. How does religious plurality factor into your work?

ANDREEA BADEA I am working on Catholic historiography and censorship in the Roman Catholic Church of the seventeenth century. When I began my research on this topic, I assumed that I would be studying a unified, corporate institution whose main aim and difficulty was to impose its own theological, political, and diplomatic views on a large number of early modern territories. My point of departure was Wolfgang Reinhard’s and Heinz Schilling’s concept of Konfessionalisierung, i.e., the assumption that after the Reformation, state, society, and church became mutually intertwined—with the result that the individual confessions became increasingly unified and uniform.

So what I was initially looking for were points in time at which “confessionalization” took place, moments when this Catholic monolith began to form and become a world religion. However, as I read more on the topic and talked to other researchers working in this field, and especially after having read the work of Simon Ditchfield, I realised that early modern Catholicism itself was a heterogeneous, multi-layered conglomerate of theological beliefs and practices, held together only by the papacy. The papacy at least had the power to bring about silence—silence about all the issues about which religious orders, theologians, and scholars disagreed.

Early modern Catholicism itself was a heterogeneous, multi-layered conglomerate of theological beliefs and practices, held together only by the papacy.

– Andreea Badea

After all, when we look closer at early modern Catholic history, we see a lot of dissent, a lot of dispute, for example, about how grace should be granted, but also about practical aspects such as dress codes within the monastic orders or about the specific beliefs of the orders. A classic example of this is the Carmelites, who were firmly convinced that they were descendants of Mary and the prophet Elijah—something that other orders and scholars vehemently denied and regarded as downright ridiculous. In order to pacify the situation, the Pope allowed the Carmelites to maintain the belief in their holy ancestry, but they were not allowed to represent this view to the outside world. In this way, the papacy—as in other disputes—acted as a judge of everything and everyone that identified as Catholic.

If we look at Italy, the region my research focuses on, there is one important point to emphasise: At the beginning of the sixteenth century, various religious groups lived there. These included several Protestant movements, which were, however, bitterly fought during the course of the century. The Curia did everything it could to standardise the Italian Peninsula in religious terms. Nonetheless, the classic narrative that the Vatican had succeeded in suppressing all forms of religious diversity and opposition in Italy by the 1580s is not true. The painstaking and continued efforts of the various local inquisitions prove this.

One of the fields that occupied scholars to the same extent as ordinary believers was historiography, which hagiography, i.e., the description of the lives of the saints, was part of. Scholars endeavoured to convince Catholics and non-Catholics alike of the importance of these “blood witnesses” for the truth of their faith. However, they did not only argue about the authenticity of the various vitae and saints. Saints were sometimes given their own agency, which is why the debates could quickly go beyond the scholarly framework and become political. These are the debates I study. My work is therefore about inner-Catholic, if you like, “inner-monolithic” plurality, which was not recognised by researchers until the late 1980s.

ALEXANDRA WALSHAM That is interesting because, of course, you find exactly the same thing happening in mid-seventeenth-century Britain: They’re fighting those on the side of the Reformation within the Reformation. So it is a fragmentation of the project of Reformation. And they are as vicious if not more vicious, against their own side, as they are against Roman Catholics.

LOUISE ZBIRANSKI It is striking that you both emphasise, when asked about religious plurality, how strongly the exact opposite desire prevailed among those who were confronted with diversity, namely the desire for religious unity.

ALEXANDRA WALSHAM Yes, there is a paradox here, isn’t there? The pursuit of a single form of truth creates the circumstances in which an enormous degree of fragmentation emerges. It is out of this pursuit of singularity, uniformity, and unity that the circumstances in which diversity becomes more widespread emerge.

LOUISE ZBIRANSKI Why is this question of uniformity so important for the social agents of the time?

ALEXANDRA WALSHAM Uniformity is important because they believe that unity is necessary for political and social order. And without that, there would be diabolical anarchy and chaos. That is the underlying assumption, which of course, is increasingly tested in the course of the period. The very fact of living with this plurality that contemporaries cannot eradicate means that they begin to have to reassess the assumption that plurality needs to be overcome. They begrudgingly admit that actually, well, perhaps, it isn’t ideal, but it is possible to live with people who hold different views. And of course, there is another irony in this—as you started out by saying, Louise—, which is that there were other periods and regions when people could live and cope with a lot more plurality. So what is it about the Reformation that actually enhances the importance of uniformity?

We often think about the history of the premodern world as a movement from persecution to toleration. But actually, it is a much more cyclical and complicated process, in which the Reformation is one further stage in that attempt to reassert the importance of uniformity. That is linked up, as Andreea said, with the forging of powerful links between religion and politics. In Britain, as in other parts of Europe, the alignment of political authority with religious allegiance creates the circumstances in which the pursuit of uniformity becomes a political as well as an ecclesiastical objective. And that, I think, makes these questions more urgent and more fraught through the period.

We often think about the history of the premodern world as a movement from persecution to toleration. But actually, it is a much more cyclical and complicated process, in which the Reformation is one further stage in that attempt to reassert the importance of uniformity.

– Alexandra Walsham

LOUISE ZBIRANSKI In terms of society, there is often an overlap between political and religious interests behind the pursuit of religious unity. But what about individual moral convictions? What about the assumption that there is a duty to lead people of other faiths onto the “right path” and thus save them?

ALEXANDRA WALSHAM Absolutely, this aspect plays an important role! There is a very strong Augustinian tradition that one has a duty to compel the wayward to return to the path of righteousness and that it is actually an act of compassion and of charity to the sinner to bring him or her back to the path of salvation. This is a fundamental principle on which acts of coercion, religious discipline, control, restraint, and what their enemies would regard as persecution rest.

This moral momentum is a very important element. I think one of the interesting questions for historians of the period is when that very powerful and paradoxical strand of Augustinian compassion as coercion gives way to the conviction that one’s moral obligation is not to persecute, but to seek other ways of resolving the problems created by pluralism.

ANDREEA BADEA In my opinion, the idea that the “heretics” needed to be saved has persisted for a very long time and without the practical problems people faced in a multi-religious world, little would have changed. I think one of the first steps on the road to more tolerance was to simply ignore it, to be prepared not to look unless problems became absolutely urgent. A good example of this is the way people dealt with church buildings. Even in cities where religious minorities were generally allowed to build places of worship, this only applied as long as their size did not interfere with the general cityscape, as long as they remained inconspicuous, were housed in private homes, etc. This was the maximum level of tolerance. Toleration was only possible as long as you did not have to see the other faith.

I think one of the first steps on the road to more tolerance was to simply ignore it, to be prepared not to look unless problems became absolutely urgent.

– Andreea Badea

LOUISE ZBIRANSKI Not so different form today’s disputes about the height of minarets or the muezzin call…

ANDREEA BADEA Another way of looking—or not looking at plurality—was the way in which the Catholics established their literary canon. They took a purely negative approach and simply created a negative canon. It was never a question of which works were right or good, but only of sorting out the wrong ones and putting them on the index—a very scholastic, Catholic approach.

Part of this approach was also an attempt to establish a quasi-scientific procedure to identify and isolate what was wrong, inappropriate, and heretical. That is the Catholic vision. And yet, even if it cannot be called tolerance, it is a first step towards dealing with the uncontrollable multitude of opinions and a first realisation that it is not possible to truly control and standardise them.

ALEXANDRA WALSHAM A very important dimension in the dynamics of religious coexistence in Britain as elsewhere is a willingness to identify certain matters that are matters of doctrinal orthodoxy, that one must hold, without which Christianity’s truth cannot be upheld. But this process involves the assumption that there is a body of other matters on which people might agree to differ. Thus, a set of religious topics emerges with regard to which people say: “Well, actually these things are not worth killing people for; they’re not worth fighting about.”

There are core matters, such as the belief in the trinity that are non-negotiable, but other things around the edges are no longer seen as so fundamental that ways cannot be found to accommodate different perspectives upon them. I think that is also an important foundation for toleration. And that same principle that there might be matters on which one disagrees then can be extended further. So ultimately, there is very little that remains around which people must unite and upon which they cannot agree to differ.

ANDREEA BADEA The Trinity is an interesting issue: What is acceptable also always depends on the context and the specific historical situation. In Transylvania, the Anti-Trinitarian Church, which denies the Trinity, was a church accepted by the Protestant communities of the early modern period. This is quite unique in Europe and is partly due to the fact that a particularly large number of Anti-Trinitarians had fled to Transylvania, but also—and above all—to the fact that the region was located on the border with predominantly Muslim areas, while in Transylvania itself the Catholic and Orthodox minorities also competed with the Protestants. Against the background of this specific religious constellation, the Anti-Trinitarians managed to become part of the German Protestant community in Kronstadt (Brașov), for example, and were able to have a say in the city councils and committees. The local Protestant communities adapted a pragmatic approach, without, however, resolving the theological dispute.

LOUISE ZBIRANSKI That also brings up an interesting methodological point: When dealing with tolerance and religious plurality, for a long time the focus was primarily on intellectual developments and the texts of the “great thinkers”. In the last 30 years, however, the focus has shifted towards everyday history and daily interaction. What are the opportunities and difficulties of such a change of perspective?

ALEXANDRA WALSHAM Well, this has, indeed, been a very pronounced trend in the last 20 years. There has been a turn away from the intellectual history of toleration, which had been the dominant approach for many, many years, towards the social history of tolerance on the ground. As a result, ordinary people have become an object of study rather than the learned philosophical treatises that are often seen as landmarks in the rise of Western modernity. Scholars have begun to try to trace and reconstruct micro-historically how communities actually lived in practice, for instance, through identifying and matching up records about who witnessed the wills of their neighbours, whom people chose to have their children baptized by or who should act as god-parents to them. These sorts of questions are increasingly being examined. And it is often assumed that those social interactions override and mitigate the intellectual differences.

I think one of the challenges of this approach is that it can sometimes lead people to invert an older model, that is to say the whiggish, teleological model that assumes it was the learned elites to whom we owe the revelation that a toleration was the way forward. In reverse, social historians of toleration are sometimes tempted to say, it was a bottom-up process of common sense and practical rationality that helped people to overcome these prejudices and ideological conflicts. So I think there can be the danger of an overly sentimental view about what social relations were like on the ground. This view, of course, appeals to our own modern sentiments. It allows us to congratulate ourselves that we are part of a tolerant liberal society. But in fact, we should not lose sight of the ongoing tensions and the latent virus of prejudice and violence that simmered beneath the surface of the social interactions. We might return to an earlier point here: one might say that actually there is a moral dilemma around whether or not you can tolerate other people.

ANDREEA BADEA And we always have to keep in mind that the majority of our sources are court records. But how likely is it that people tell the truth in front of a judge?

ALEXANDRA WALSHAM Yes. And we are often reading them against the grain.

ANDREEA BADEA And then, of course, the question also arises as to why certain things were tolerated or simply overlooked for years and years and then suddenly end up in court... It is precisely these moments when tolerance becomes fragile again, where we must take a closer look and ask ourselves: What was the previous getting along with each other based on and why is it suddenly no longer possible? What are the reasons for this?

ALEXANDRA WALSHAM There are obviously some sources that alert us to these matters in a more indirect way.

I think of Catholic casuistry, of cases of conscience that are trying to decide what you should do in particular situations, for instance, if your Protestant neighbours come to dinner. What should you do? Should you serve them? If they start expostulating against the church of Rome over the dinner table, are you supposed to reprove them? Or should you just turn a blind eye and a deaf ear to this?

The other thing that may be worth underlining is that, of course, to tolerate in any society, is to refrain from acting in a way that you believe you ought to, i.e., to restrain their falsehood. It is an act of omission. It is an act of overlooking, enduring, and indulging the conduct of other people for whatever reason. So it is methodologically challenging for historians to reconstruct this toleration, because it lurks in the silences and the gaps. Therefore, there is a danger of overreading the significance of those gaps and those silences and inferring too much about motivation, when often that motivation is not articulated.

Tolerating is an act of omission. It is an act of overlooking, enduring, and indulging the conduct of other people for whatever reason. So it is methodologically challenging for historians to reconstruct this toleration, because it lurks in the silences and the gaps.

– Alexandra Walsham

ANDREEA BADEA During your stay in Frankfurt, you talked about the question of politeness, which is closely related to practices of not-looking.

ALEXANDRA WALSHAM Yes, it’s an interesting juxtaposition, isn’t it? Because politeness is something we associate with the effort to create smooth and good social relations. But politeness carries its own undercurrent of disapproval and its own ways of marginalizing people. It marginalizes people through differentiating between who is polite and who is not polite, but also in more subtle ways: by excluding those to whom politeness is shown, those whose “bad behaviour” you pretend not to see.

Though we might sometimes think we see an increase in toleration or politeness through time, as a historian I tend to be resistant to narratives that celebrate progress towards modernity, towards a nearly liberal society. I have always wanted to recognize the complexities, the ironies, and the tensions that remain—after all, so much of what happens in modern twenty-first-century politics and news is a further illustration of the circularity of these processes in every society.

ANDREEA BADEA I think this last point is very important. In Germany, too, there is a kind of “Whig history” that put forward the idea that the early modern period was the laboratory of modernity, that everything that happened in those 300 years was actually just an experiment for a better society. But this narrative does not work.

LOUISE ZBIRANSKI Although, paradoxically, I think that precisely this circularity, the reappearance of problems, can certainly be an argument in favour of looking at the early modern period as a laboratory and asking how these problems were dealt with back then and what the situations have in common that the issues are now reappearing—which also leads to the last major question: It has been alluded to before with regard to record of court cases as historical sources: There are often phases in which a certain form of seemingly religiously deviant behaviour, which initially hardly plays a role, has been “overlooked” for quite some time until suddenly it becomes a problem. What is behind these dynamics? In particular: To what extent are they related to the fact that these actions do not simply take place, but are also named and categorised and thus suddenly also stand for publicly identifiable groups?

ALEXANDRA WALSHAM There are very important elements in this question: On the one hand, the “orthodox” themselves identify themselves as “orthodox”, as true believers, and see the task of identifying, naming, and making visible error as vital. There is a huge and rich historiography from the Middle Ages onwards, about how minority groups, groups identified as deviant by the “orthodox”, come into being partly through the process of being identified and named. There is dialectical process by which things do not exist until they are named. But that process of naming catalyses a sense of identity within the group so named. Language, written and spoken, is vital in entrenching this pluralism and identifying its presence in society.

What is enormously important, on the other side, is the willingness of certain people to refrain from using names, to refrain from casting vicious words against their neighbours. That creates the conditions in which coexistence can germinate and grow. That is the theme that I try to explore when I look at the dynamics of speech and silence. It is as important to understand what people do not say, as what they do say, as both have the capacity to foster toleration, and also at the same time to create the conditions in which those outbreaks of intolerance and violence can re-emerge in any given society.

These are questions we pose ourselves again today, when we talk about free speech. This is a challenging area, but one might say that the current climate is one in which it has become difficult for people to accept that opinions that they do not share are opinions that other people should be allowed to air and articulate. Where is that boundary between offending and accepting differences of opinion to be drawn? I think we are in midst of one of these periodic recalibrations of the precise location of that boundary. The questions that people were tearing themselves apart about in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries remain fundamental to how we respond to social innovations and developments now, just as they were then.

Tolerance as an ideal sometimes runs against the concern that actually tolerance might be offensive and might be itself corrosive of social relations. And if we sometimes may have the impression that that a kind of intolerance towards tolerance is evolving, historians will remind us that this is not new, it is simply another phase in the ongoing cycle in which these things are renegotiated at different points in history.

ANDREEA BADEA However, it seems to me an exciting point that there is so much discussion today about the difference between hate speech and free speech. This distinction was not so important in the early modern period. What we understand as free speech today would have been an attack against the social order in itself and would therefore have been prevented by the sovereign.

The distinction between hate speech and free speech was not so important in the early modern period. What we understand as free speech today would have been an attack against the social order in itself and would therefore have been prevented by the sovereign.

– Andreea Badea

ALEXANDRA WALSHAM I think another difference is that in the early modern era, there were situations in which people regarded it as their moral obligation to actually speak against others and reprove other people in a form, which from our modern perspective could be seen as hate speech. It goes back to the concept that I constantly returned to, that of charitable hatred, the notion that the hatred you have, is a charitable hatred: It is driven by convictions about your moral and your spiritual obligation to reclaim your neighbours from hell or from divine judgment.

LOUISE ZBIRANSKI I think one question that plays a much bigger role in the premodern era than it does today is not only what you are allowed to say or write, but also who is allowed to hear or read it. In my opinion, Andreea, your work on Catholic censorship is a good example of this.

ANDREEA BADEA If we look at the Roman Curia’s indexing practice, it is of course striking that what is indexed was not forbidden to everyone. Lawyers, theologians, doctors, or nobles were generally given access to banned books. There was this idea that education and knowledge conferred moral strength. This was based on the very Catholic distinction between the public, who were not allowed to participate in certain contexts of knowledge because they did not have the appropriate education, and the scholars, who were allowed to do so. The classic example is Galileo. His case was not a matter of right and wrong, the contents of his thoughts were not forbidden per se, they were just not to be available to everyone. The assumption behind this was that large sections of the public were simply not in a position to understand that parts of the Bible were to be understood metaphorically and not literally. It was about “protecting ordinary people”—an idea that has rightly become very alien to us today. However, the question of what happens when scientific insights enter the public debate without being sufficiently contextualised is certainly one that also arises in the present day.

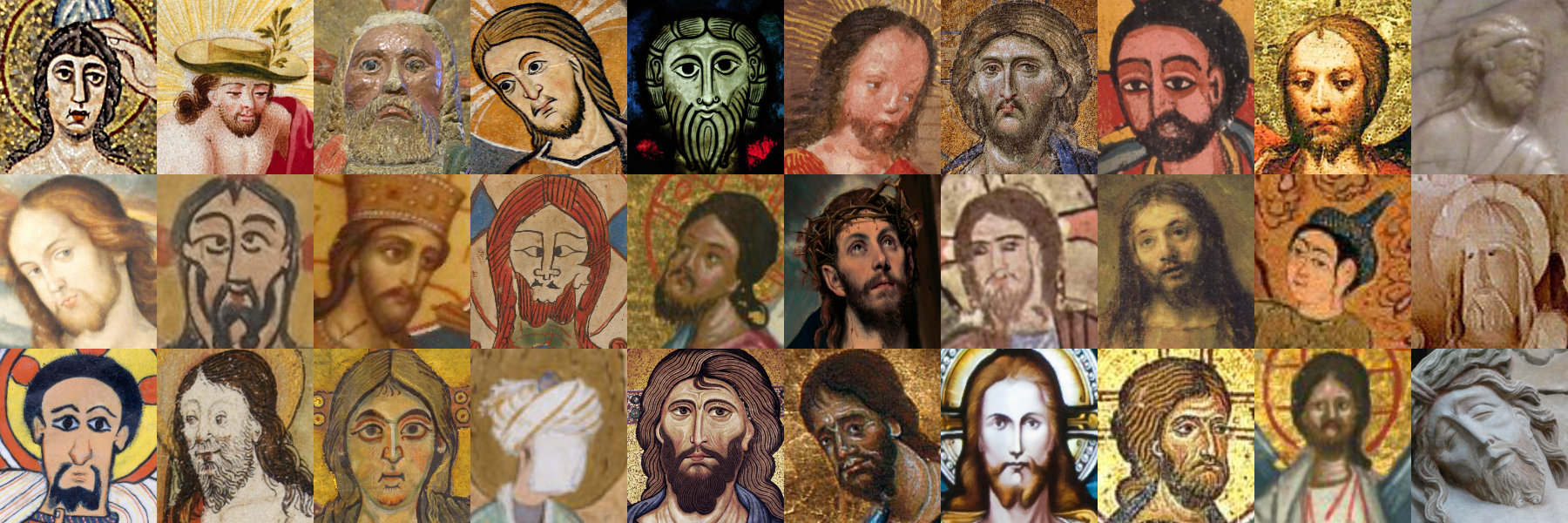

About the image: The image is a composite using various pictures of Jesus from the medieval and early modern periods. All images were sourced from Wikimedia Commons. These images depicting historical works are without copyright restrictions, or have been made freely available by the copyright holder. The following list contains information for each image: the name of the image, its source URL, licensing information, and (where possible) the copyright holder.

First row, from left to right

Second row, from left to right

Third row, from left to right

Further News